Lawrence M. Schoen sends us a stand alone story from the Amazing Conroy universe, featuring Conroy’s friend the professional gambler known as Left-John Mocker. It first appeared in the December 2006 issue of nanobison — ed, N.E. Lilly

Texas Fold’em

Like sensible folk, Left-John Mocker stayed out of Texas. Mostly. He made an exception for Smokin’ Sam’s card house in Amarillo. The Mocker played cards for a living, and Smokin’ Sam’s held his luck. Or so he had come to believe.

In all other things Left-John was the pinnacle of rationality. He’d cashed in on the stereotypical stoicism of his Comanche heritage and honed a poker face that gave nothing away. Day to day, game to game, and card by card, he didn’t believe in superstition. But luck was something else entirely. Every few years he returned to Sam’s, like some kind of recurring Hajj, responding to a call that he alone heard.

The Mocker crossed the border from Oklahoma, leaving the United States behind and entered the Standalone Star State. Texas had been expelled from the union after an experimental chrono-schism pulled it out of the normal time flow. Amarillo hadn’t been hit too hard; the ratio generally hovered around twenty to one. Left-John had three weeks before he had to be back in Jersey, which — factoring in a safety buffer — gave him a full six hours of play.

Despite the slow time, the card house had a fresh selection of regular players every time he visited, as well as a new “Sam” managing the place, a fluke of some house policy. About the only familiar faces he encountered, time after time, were the dealers. They never seemed to move on.

From the outside, Smokin’ Sam’s looked like a family restaurant abandoned after a fire, which in fact it was. The stuccoed walls were black with soot and char, the windows boarded over with dark wood and urban runes. Inside, every bit of fire damage had been repaired and every indication of family dining removed. The lingering scent of smoke came from locally grown tobacco.

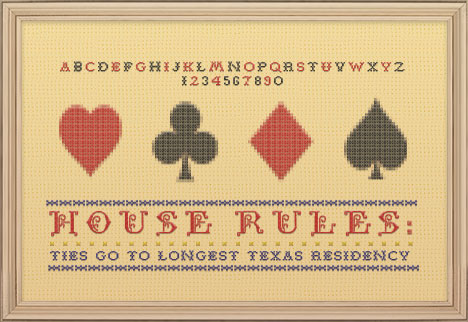

Sam had replaced the burned and blistered booths of the restaurant with half a dozen round tables, each topped with green felt and surrounded by eight captain’s chairs. Track lighting gave full illumination to anyone seated at those tables and left the rest of the interior in shadow. An old fashioned bar complete with brass foot rail ran along the back wall. A handful of waitresses wearing engine-red hot pants, matching half tees, and singed fire-fighter helmets roamed the room serving drinks. A cigar store Indian wearing a pair of opaque sunglasses stood just inside the door. Above its head a needlepoint sampler read

A fat man stood to the side of the wooden Indian, reeking of cologne that seemed two parts bourbon and one part swamp gas. He wore a flashing name badge that entreated one and all to “Call Me Sam,” and he stopped Left-John Mocker almost before his eyes adjusted to the gloom.

“You can’t play here,” said Flashing Sam. He stood a head and a half shorter than Left-John and had positioned himself so close he had to tilt his head back, revealing that his thick yellow moustache had its source in his nostrils.

“You discriminate against Indians?” said the Mocker, his face as stone cold as when he lay in bed asleep or sat at a high stakes tournament.

“’course not, Indians are welcome. Pros are another matter.” Sam held up a data padd. An image of the Mocker appeared above his name on its tiny screen, along with his ranking in the Probability Guild. “You’ve got jazz master status,” said Sam, “a double-Coltrane rating. If I let you play here you’ll clean out my regulars and move on to your next hustle. No thanks.”

“I play here all the time,” said the Mocker. “You must be new. Where’s Sam?”

“I’m Sam,” said Flashing Sam, and pointed to his badge like a sheriff’s star. “The last Sam ran off to Tierra Del Fuego with the beer distributor’s daughter. This is my place now, and I don’t allow no guild members to play here.” He took a step back and regarded the Mocker with a well rehearsed sneer, then nodded his head toward an obvious security camera. “And don’t even think about coming back in disguise when I’m not here, cuz the facial recognition software will pick you out easy as aces. You’ve been logged and you’ve been warned. You show up again and there won’t be no friendly chat like now. Got it?”

“Got it.” Left-John paused, not considering but not leaving. He paused because even without cards this was still a card game, because he was still holding something, and because there was a pot that he wanted and wasn’t ready to give up on. He paused because, being who he was, he knew that there are times in any game for quick action and times to suspend all motion. This was one of the latter. He watched Sam tense and fidget a bit. Agreeing with the man had partially disarmed him; following that up with not leaving had further confused him. Left-John Mocker could almost see the man working it all through and just before Sam reached a decision the Mocker asked, “What if I promise not to win.”

“Huh?”

“What if I promise not to win. I just want to play here, Sam. I don’t need to win.”

“Bullshit! You’re shiny.”

“Shiny.” The Mocker repeated the word with an intonation between question and statement, irony and amusement.

“Shiny as a caddy fresh from the carwash with a slow hand carnauba job,” said Sam. “You’re holding a double-Coltrane rating. You can’t help but win. Nice joke. I never met a pro with a sense of humor before.”

“What if I give you my word that I won’t win.”

“You can’t,” said Sam, snorting.

“Excuse me?”

“Even a pro can’t control random chance. That’s what makes it a card game. A guild member’s word is sacrosanct in a licensed card house; you won’t promise something you know you can’t deliver.”

Left-John Mocker nodded. “Ah. That is a point. Well, then I’m down to my last chip.”

“If you’ve got another play I’ll hear you out. You’ve been more amusement than I expected from you.”

“What if I cut you in? No risk to you, only profit if I win.”

Sam stopped, everything but his badge. He froze like a bull that’s been whacked in the head with a hammer and doesn’t know it’s dead. When movement resumed it started in his hands. One began making a circular stroking motion that started on either side of his moustache and traced the shape of his mouth, which hung partway open. His other hand dug in the front pocket of his jeans and worked at something it found there. The Mocker said nothing, merely catalogued the man’s mannerisms with a choreographer’s eye and filed them away with a mental note that whatever else he might be, Flashing Sam was no card player.

“What’s the cut?” said Sam.

“Fifty percent.”

“Ninety.”

The Mocker almost smiled; almost. “Why would I bother to play for only ten percent of the winnings while assuming one hundred percent of the risk?”

“Your reasons don’t concern me none. A minute ago you were begging to play just so you could lose. What does it matter if instead of losing you only get a tenth of your winnings? Do you want to play here or don’t you?”

“I do. Ninety percent it is. We have a deal.”

Sam wiped his right hand on his hip and stuck it out in front of the gambler. “Shake on it.”

The Mocker looked at the hand and then shifted his gaze to meet Sam’s eyes. “You’ve got my word,” he said. “You don’t need my hand. Now get out of my way and find me an open table; I’ve got to get back to Jersey by the end of the month.

Two minutes later Left-John Mocker had traded cash for chips and pulled up a chair at one of the high stakes Hold’em tables. Sam hovered over the table’s dealer as he introduced the Mocker to the other players, noting both his membership in the Probability Guild and his jazz master status, babbling on about what a rare privilege and opportunity this was for everyone at the table. Left-John Mocker remained silent through all of it. He nodded to the dealer, a tall drink of water whom Left-John remembered as having been the managing Sam on a previous visit, but whose name tag read Buck. The dealer returned the nod and Left-John turned to study his opponents, all the while rolling a thousand dollar chip back and forth over his fingers.

Several of the other players were pensioners, people who popped over the border and out of the chrono-schism just often enough to pick up their monthly retirement checks, cash them, and then blow them in a single day’s gaming in slow time. Under more normal circumstances, Left-John Mocker didn’t play against pensioners, which was yet another reason he usually stayed out of Texas. Taking their money just left him feeling unclean.

But this was Smokin’ Sam’s, and he never won here. That was the point. Left-John Mocker had won games and tournaments at every major card house and casino in Human Space. He knew nearly one hundred different card games, and he could win at every one of them. But not at Smokin’ Sam’s. He kept his luck here. His bad luck.

When it came to luck, Left-John didn’t take the good with the bad. He set the bad aside, stored it up near to bursting, like the proverbial camel, one straw short of a chiropractor, saving it for Smokin’ Sam’s. Left-John had come to lose and lose and lose and lose some more. He intended to keep losing until he drained the bad luck out of him, so that when he sat down at every other gaming table anywhere else, he could win. Whether it was because of the Texas chrono-schism or just something about this particular card house that he’d made holy in his own mind, something impossible happened here and nowhere else. Rationality met superstition here, and the replicated outcome produced faith. The rules of probability and the law of large numbers met anecdotal evidence, and fell like a casualty of some statistical war. Left-John Mocker had come here to lose, no matter how much he might have to work to do it. A lifetime of professional card playing guaranteed it would be difficult.

Think about it. Ask the first chair violinist of a national orchestra to play an entire performance with an out of tune instrument. Demand a poet laureate to spend an evening speaking in ribald limericks only using single syllable words. Insist that a master painter grip a brush between the cheeks of his ass and fill a canvas, knowing it will hang next to his greatest masterpiece in some museum. Or simply consider these things, and then feel pity for Left-John Mocker, whose talent and gift and reason for living was to play cards and play well.

He worked hard to lose. He bet when he had nothing, checked when he should have raised, and reraised a check-raise when he should have folded. Throughout Human Space he knew five hundred players who could have seized on any one of these patterns and stripped him of his bankroll in short order. Alas, none of them were present. The players seated at his table didn’t believe him.

Instead, they clung to the illusion that he operated under some hidden purpose, convincing themselves they’d misread some subtle detail in the pattern of wagers, or that he was setting them up for a hustle. They retreated from his pointless raises, threw away winning hands, surrendered the blinds to him again and again. With the result that instead of losing, the Mocker won hand after hand.

He strove harder. He invented tells, little gestures that he hoped would appear to be subtle but still noticeable. He drummed his fingers whenever he’d been dealt a pair. He rubbed the bridge of his nose when he bluffed. He yawned and stretched like the king of the forest when he held an unbeatable hand.

And still the other players refused to believe, refused to act on a cornucopia of clues and signals and signposts. They ignored his drumming fingers, folded more often than not when he rubbed his nose, and reraised him over and over with every yawn. And most of the time, they lost. Most. Once in a while, perhaps one time in ten, the random nature of the cards would cause one of them to win a hand, and they would all nod with vindication that they had played him right, no matter the evidence of their dwindling stacks of chips.

After two hours at the high stakes table the Mocker was up more than four hundred thousand dollars, which likely elated Flashing Sam, but did nothing to improve his own mood. Left-John’s plan of accruing bad luck had acquired its own exceptional streak of bad luck, which he doubted counted toward the winning outcomes he needed in the gambling halls beyond Texas.

Play continued. A small crowd of onlookers gathered around the table. Most of them had never seen a ranked Guild member, let alone a double-Coltrane player. There were a couple locals, not regulars or pensioners, who remembered him from previous trips. They hung back, sharing winks and smirks, making side bets with the onlookers who took their wagers with embarrassed glee. As time wore on and the Mocker continued to win, they started looking worried.

During the third hour, and despite his best efforts to lose, Left-John Mocker cleaned out three of his opponents. And damn him if they didn’t come around to his seat to shake his hand and thank him for the pleasure of giving him their money. The tiny throng cheered the losers as each retired from the table. They were ordinary card players who had sat at a table with a Guild member and maybe even won a hand or two, elevating them to celebrity status. Fresh players vied with one another for the privilege of buying into the table each time a seat opened, as if they too longed for the distinction of losing to him. People can be funny like that.

After four hours of play, Left-John Mocker had won more than seven hundred fifty thousand dollars. Only two hours remained, and far from simply losing his initial stake, he had to lose all his winnings as well. It didn’t seem to matter what he did, he still won. Realizing this, he resolved to try one last gambit, and do nothing.

When Buck dealt the next hand, the Mocker didn’t bother to look at his cards; when play passed to him he simply bet half the value of the pot. His opponents stared, silent and confused, and even their starstruck minds knew this could not be a trick. Two of the players in line after him called his bet; one raised. The Mocker saw the raise. Play progressed and he still left his cards untouched. After the flop he bet, was raised, reraised himself, was reraised in turn, and called. He bet at the turn, and again at the river, and when he flipped his cards at the showdown he finally saw them at the same time as everyone else: a trey and six, off suit. One of his opponents had a full house, Queens over nines. Another had a straight. The Mocker with only Queen high crap, had managed to put nearly forty thousand dollars into the pot. And he’d lost. Finally, and substantially, he’d lost. His prospects looked brighter.

He played the next several hands the same way, betting his hole cards unseen, raising and reraising until the showdown. He lost over one hundred seventy thousand dollars and began to breathe easier.

The next hand had Left-John on the button and thus last to bet. As play moved around the table several players bet. Left-John reraised and, despite having seen him lose the last five hands, all but one of his opponents folded, and that one reraised him. When it came around to him, but before he could call or re-raise, again without glancing at his cards, the remaining player raped his knuckles on the table to get Left John Mocker’s attention.

“Pardon me for saying so, Mr. Mocker, but you’re taking all the pleasure out of the game.” The speaker sat halfway around the table from his left, a middle-aged cowboy who’d kept his black Stetson on when he replaced one of the pensioners at the table more than an hour ago. Buck had introduced him as Earl.

“How’s that?” said Left-John as he played with his chips, making a series of fifty thousand dollar stacks.

“There’s no heart in what you’re doing, in the way you’re playing. Are you having a go at us? Looking down your nose cuz we’re just card players without so much as a jazz rating among the lot of us?”

Left-John stopped stacking his chips. He tipped his chin up a few degrees. “And what if I am?”

Earl put his hands on the table, palms down and said, “if I thought that, if I thought any man here was using me for sport, let alone using all of us that way, well, I think Texas honor would require me to whup that man’s ass to remind him where he was.”

The Mocker allowed himself an internal smile that never made it to his lips. “Then it’d be pretty stupid of me to be doing that.”

“Yep,” said Earl. “And a man don’t rise to your level in the Probability Guild being stupid, so tell us what you’re really doing.”

There’s a moment that any professional gambler can tell you about, a moment when you can feel Lady Luck behind you, pressing her generous endowments against your shoulder blade and breathing hotly into your ear. Left-John Mocker had felt that moment many times before. He’d known it at gaming tables in Rio and in Belfast. He’d ridden it during a tournament on Brunzibar. He’d grasped it and felt it slip from his fingers during the last round of play at the Clarkeson embassy on Burke’s world. He recognized it now, perceiving it as a faint sensitivity in the tips of his fingers and an awareness at the base of his neck. No doubt about it, Luck was with him. But could he could trust it? This was Texas and Smokin’ Sam’s. This was the home of his luck. He’d never felt the Lady here before, and it occurred to him that under the circumstances she could be a real bitch.

The gambler gambled. “I’m looking for you, Earl,” he said. “You called my bluff. That’s the kind of stones I came here to see. There’s just one more test, to know for sure.”

“What’s that?” said Earl.

“Whether or not you’ll call me when I go all in now.” Left-John pushed the remainder of his chips forward, more than six hundred thousand dollars worth.

If Left-John had been the game’s big winner, Earl had been the little one since he’d joined the game. He’d done well, but he didn’t have that much in front of him, not by a long shot. Earl looked to Sam, and a nod passed between them that told everyone at the table that Earl was good for it.

“If I call you, I clean you out,” said Earl.

“If you call and win,” corrected the Mocker.

“If I lose, I’d be giving you almost everything I have in the world.”

“That happens a lot in poker.

“You still ain’t looked at your cards. You’re just living up to your name, and mocking us again.”

“My bet’s in,” said Left-John. “There’s no mockery in the pot, just a bit of my money, and all the money I’ve won from everyone here. You’ve looked at your cards, and all you have to decide is whether you think you can win the hand.”

Flashing Sam slipped around the table, midway between Earl and Left-John Mocker. “That’s the biggest pot we’ve ever had since I’ve been Sam.”

“You think that’s gonna scare me off?” said Earl.

“It shouldn’t,” said Left-John. He’d locked his gaze on Earl and held the other man’s eyes. “There’re only three things that matter, and only two to worry about, when you’re in a heads up situation.”

No one spoke. It was like none of the other players or the men and women crowded around the table even existed. Earl didn’t so much as blink. “You gonna say what they are?” he asked, breaking the silence.

Left-John held up a single finger. “Your cards.” He raised a second digit. “And what your opponent’s thinking.”

“You said three things,” said Earl.

“But only two worth worrying over. The third you can’t do anything about.”

“What is it?” said Earl.

“Luck,” said Left-John, “and it’s taken down every Guild member more than once.”

“I’ll call,” said Earl. Flashing Sam handed him a data padd. Earl punched the keys and transferred the full amount of his savings into the padd and slid it to the center of the table with the rest of the wager. “What have you got?”

The Mocker turned over his cards, deuce and seven off suit.

“Beer hand,” said the player to Earl’s left.

Earl revealed his own cards, ace king suited. “Big Slick,” said another player. “Best and worst hands in the game.”

“Doesn’t mean anything,” said Flashing Sam. “The flop could be three sevens. I’ve seen it happen.”

The dealer nodded to both players and revealed the flop, five, six, and eight, all spades, the one suit neither player had.

“That’s no help to any one,” said Flashing Sam.

“The Ace is still high card,” said Buck.

Earl gave a nervous nod and Left-John allowed himself to smile. “Let’s see the turn,” he said.

Buck revealed the fourth common card, a four of spades.

“He’s got a straight,” said Sam, his whole body practically deflating with relief.

Earl frowned. “Your three things was my cards, what the other player’s thinking, and luck,” he said. “We can see each other’s cards. What are you thinking about?”

“I’m thinking about luck,” said the Mocker.

Buck looked first to the Mocker and then to Earl before flipping over the river, the final common card. It was a seven of spades.

“It’s a draw,” said Flashing Sam, blinking in disbelief. “They both have the same straight flush. They split the pot.”

Buck shook his head. “Not here. House rules: no draws. Longest Texas residency wins.”

“I’m from Oklahoma,” said Left-John. “Where are you from, Earl?”

“New Mexico,” said Earl. “I ran into some trouble — a misunderstanding, you know how it is — and moved here about two years ago.”

“Beats me,” said Left-John. “I’ve only been here the past few hours. Congratulations.”

Earl looked stunned. “There’s close to two million in the pot. I never won that kind of money,” he said.

Flashing Sam slammed his hands flat on the table. “What are you talking about? That sign by the entrance? That’s just decoration. It’s a draw. They split the pot.”

Buck shook his head. “Check your contract. It’s in the fine print, under binding traditions and customs. I didn’t pay any mind to it myself, back when I was Sam.”

“You were Sam?” said Earl.

“Yep, until someone won a big game on a draw hand and invoked the house rule. He bought me out with his winnings. That was five or six Sams ago.”

Earl’s face lit up. “Could I do that? Buy Sam here out?”

“Why would you want to do that?” asked Left-John.

Earl shrugged. “I’ve just beat a double-Coltrane guild member for the biggest pot of my life. I don’t think it’s going to get any better. Might as well go out on top. I can’t imagine ever getting that lucky again.”

Left-John pushed back his chair and stood up. He had just enough money tucked away in his back pocket to get him out of Texas and back to Jersey. “You never know,” he said. “Luck can be funny that way.”

♠

I Love Serenity

Men’s Basic T-Shirt that says “I Love Serenity” in Chinese.

Available from the Space Westerns Magazine Store on Zazzle →

Comments

You are not logged in. Log-in to leave a comment.